The Debt Oklahoma Owes: How the State Leaves Counties High and Dry

Broken Promises and the Burden on Oklahoma’s Counties

By Marven Goodman, March 4, 2025

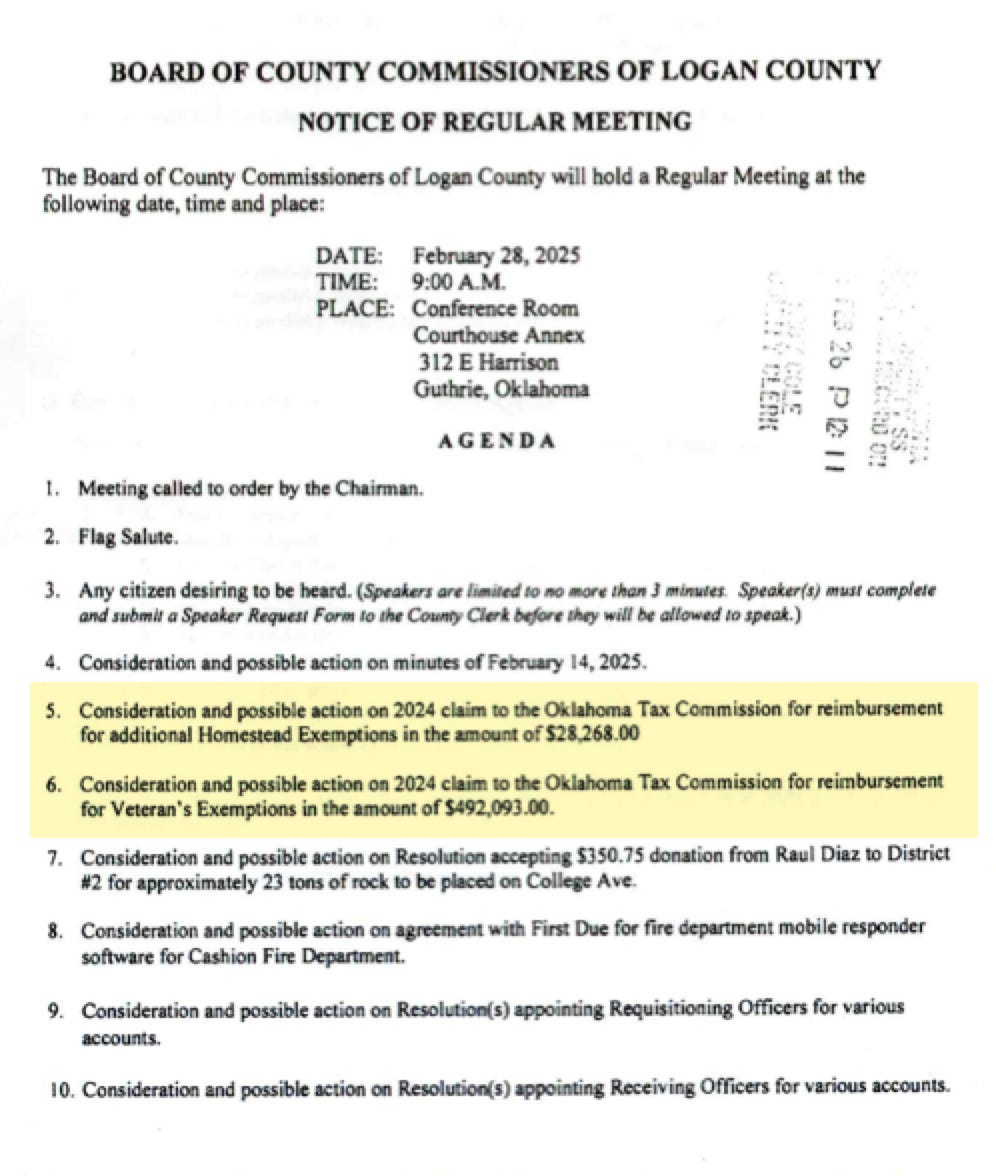

On February 28, 2025, the Logan County Commissioners convened in their Guthrie courthouse, a weathered testament to Oklahoma’s pioneering spirit. The agenda plodded through routine items—until County Clerk Troy Cole laid bare a festering issue. Two requests to the Oklahoma Tax Commission (OTC) stood out: $28,268 for Homestead exemptions and $492,093 for Veteran’s exemptions, totaling $520,361 in tax breaks Logan County covers but never recoups. “We always ask for these reimbursements,” Cole said, her tone laced with weary repetition, “but the state never pays.”

From the forested ridges of Adair County to the sprawling plains of Tillman, Oklahoma’s 77 counties face a quiet fiscal squeeze. The state vows to repay them for tax relief and disaster costs—money for roads, bridges, and sheriff’s offices. Yet the funds falter. Logan’s $520,361 shortfall is one piece; disaster relief adds another. When FEMA covers 75% of storm damage, the Oklahoma Department of Emergency Management (OEM) owes 12.5%, and counties pick up the final 12.5%—100% in principle. In practice, OEM’s share lags, piling onto a broader pattern of underfunding by the Oklahoma State Legislature. Why does Oklahoma promise what it won’t deliver, and how are counties bearing the brunt?

The Exemption Squeeze

Logan County’s $520,361 deficit stems from two tax breaks. The Homestead exemption (68 O.S. § 2889) cuts $1,000 off a home’s assessed value—about $80 to $120 annually—for resident owners. The Veteran’s exemption (68 O.S. § 2892), enacted in 2005 and solidified by a 2006 vote (State Question 725, 67% approval), eliminates property taxes for 100% disabled veterans and their surviving spouses. Both lighten taxpayer loads, but they chip away at the ad valorem tax base counties rely on for roads and public safety.

For Logan, with a 2023 valuation of $750 million and a $8.2 million general budget, that $520,361 loss—6.3%—could fund six deputies or resurface miles of Broadway between State Highway 33 and Waterloo Road. The setup? Counties grant the breaks, report losses to the OTC (Forms 921 and 998), and the state reimburses. “It’s supposed to happen,” a Logan official says, citing 68 O.S. § 2892. “But ‘may’ reimburse isn’t ‘shall,’ and the cash never lands.” In 2025, Logan’s $28,268 Homestead and $492,093 Veteran’s claims—driven by its veteran-rich rural appeal—sit unpaid.

Why? Oklahoma’s budget hinges on oil—29% of revenue in peak years like 2014, per State Treasurer data. When prices dropped to $26 a barrel in 2016 (vs. $80+ in 2022), cuts hit hard. Education, health, and prisons stayed afloat; county aid drowned. A $1.2 billion surplus in 2024 could’ve covered it—$15 million statewide in 2023 exemptions, per Legislative Office of Fiscal Transparency—but didn’t. “It’s not a vote-winner,” an Oklahoma City budget analyst says. “Tax relief gets applause; county shortfalls don’t.”

Disaster Dollars Stretched Thin

Disaster relief echoes the pinch. Oklahoma’s storm-prone heart—16 counties struck in 2024 (FEMA declaration, June 4)—relies on FEMA’s Public Assistance grants: 75% of costs like road or bridge repairs. OEM owes 12.5%, counties the rest—12.5%—totaling 100%. In Hughes County, a 2023 flood trashed a bridge: $2 million to fix. FEMA’s 75% is $1.5 million, OEM’s 12.5% is $250,000, and Hughes’ 12.5% is $250,000—$2 million, dead on.

But OEM’s $250,000 often arrives late—or not at all. “We front the work,” a Hughes commissioner says. “FEMA pays fast; the state stalls.” Hughes got $1.5 million from FEMA, but with OEM’s share delayed, it shelled out $500,000 upfront—double its 12.5%—until reimbursed. Statewide, these lags cost millions yearly. OEM’s $10 million FY 2024 budget depends on general funds, and when oil dips or lawmakers flinch, that 12.5% wavers. “FEMA’s reliable,” an Oklahoma City budget analyst says. “The state’s the holdup.”

Unlike exemptions, where funds vanish, disaster aid’s a waiting game—promised but tardy. “It’s still underfunding,” a retired county treasurer says. “Counties borrow or delay, eating interest or leaving roads rutted.”

A Legacy of Half-Kept Vows

This isn’t a glitch—it’s a groove. In 2005, HB 1683’s Veteran’s exemption came with a reimbursement pledge (The Oklahoman, 2005). SQ 725 in 2006 doubled down. Homestead’s older, with the same nod. Yet budgets from 2010–2020 (Oklahoma Office of Management and Enterprise Services) show spotty funding—often zero. “May” reimburse, not “shall,” is the escape hatch (68 O.S. § 2892). OEM’s 12.5% disaster share, built into its role, hits the same wall—appropriations fade when priorities shift.

Counties keep asking—Logan’s $520,361 in 2025 mirrors past years. “It’s routine,” a Logan official says. “We file, we nudge, we signal effort.” Hope’s dim. Politically, it’s low-risk—voters love vet breaks (67% in ‘06) and disaster aid, not county deficits. “Big counties like Tulsa can stretch,” an Oklahoma City budget analyst notes. “Rural ones bleed.”

The County Crunch

Adair County felt it in 2024. A tornado buckled a county bridge—$800,000 to rebuild. FEMA’s 75% ($600,000) landed, but OEM’s 12.5% ($100,000) lagged six months. Adair’s $100,000 share doubled to $200,000 upfront, straining its $250 million valuation. “We skip gravel runs,” an official says. Logan’s $492,093 Veteran’s hit—tied to Guthrie’s pull—means fewer deputies or potholes linger on Broadway between State Highway 33 and Waterloo Road. Statewide, $15 million in 2023 exemptions plus delayed disaster funds (millions more) pinch lean budgets. “It’s not charity,” a retired county treasurer insists. “It’s what’s due.”

Why It Endures

The Legislature’s the pivot—73% GOP in 2025, keen on tax cuts (2024’s income tax trim) but coy on funding them. Oil’s boom-bust—$1.5 billion in FY 2014, half in 2016—starves stability. “They fund what’s loud,” an Oklahoma City budget analyst says. “Schools, Medicaid—visible. Counties? Silent.” A 2024 $1.2 billion surplus bypassed relief. Statutes enable it—“may” offers leeway; OEM’s delays roll on. “No one’s fighting,” a former lawmaker says. “Counties lack clout.”

Texas contrasts—Proposition 1 (2023) funds veteran breaks via a steady pot. Oklahoma’s patchwork falters. “It’s structural,” a retired county treasurer says. “Promises, no follow-through.”

A Fix in Sight?

Options hover. A bill could mandate a fund—sales tax ($3 billion yearly) could cover $15 million in exemptions and OEM’s $2 million disaster share. Counties might sue over SQ 725’s intent, though “may” muddies it. Hiking millages—Logan’s 105 mills could inch up—risks voter ire. “We’re stuck,” an Adair official says, “unless lawmakers step up.”

In Guthrie, the courthouse holds steady. Logan’s $520,361 fades to ledger dust. Hughes waits on OEM. Adair bridges groan. Oklahoma touts aid—vets, disasters—but counties shoulder the load. As storms brew and families settle, the state’s debt lingers—a pledge half-kept, a trust worn thin.