Oklahoma’s Stand Against Federal Overreach: Logan County’s Storm-Water Plan Sparks State’s Rights Debate

Logan County’s Clash Over Federal Mandates and Local Control

By Marven Goodman, June 18, 2025

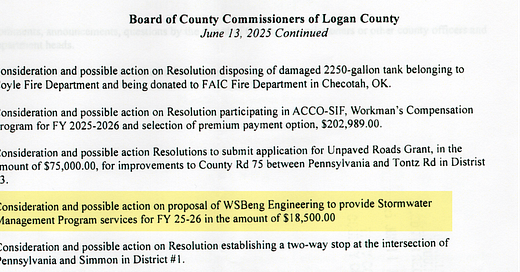

In Logan County, Oklahoma, a showdown over federal overreach is brewing over the June 13 agenda item, which eventually died due to a lack of a motion to accept the proposal, yet sparked a lively debate. At stake is a proposed $18,500 sole-source contract with WSB Engineering to draft a “minimal” storm-water management plan, purportedly to satisfy federal requirements imposed by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) through the Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ). Pushed by Logan County Clerk Troy Cole and District 1 Commissioner Mark Sharpton, the plan aims to comply with the Federal Clean Water Act (CWA) mandates for urbanized areas, but it faces staunch opposition from District 3 Commissioner and Board Chairman Monty Piercy, who champions local control.

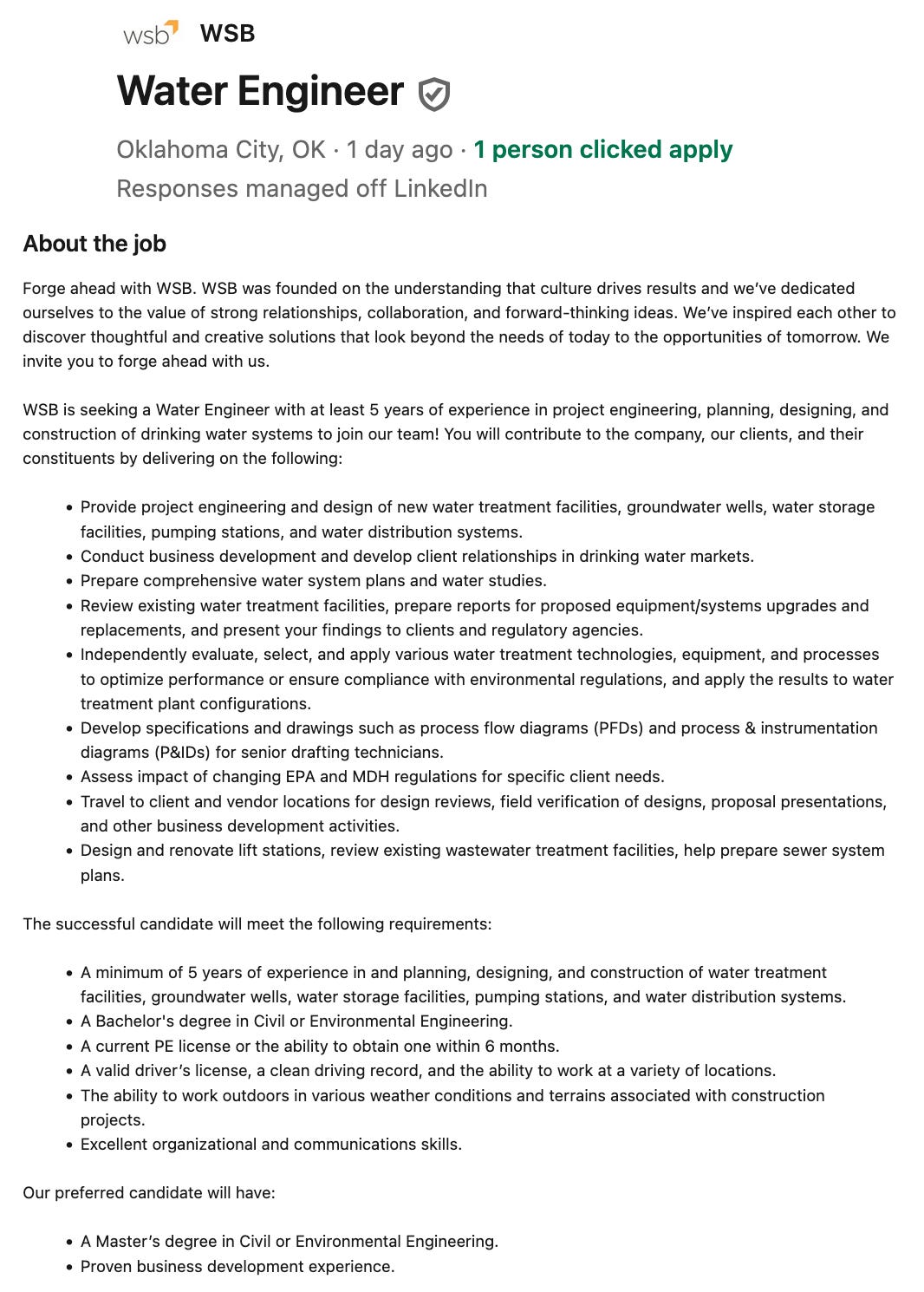

Adding fuel to the fire, WSB’s June 13, 2025, LinkedIn job posting for a Water Engineer in its Oklahoma City office hints at expected growth from such mandates, coincidence or calculated profit? As the Logan County Board of Commissioners debates this expenditure, the U.S. Supreme Court’s June 28, 2024, Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo decision offers Oklahoma a chance to resist federal bureaucracy, raising a critical question: will Logan County bow to EPA/DEQ pressure or stand firm for sovereignty?

The Federal Yoke: EPA, DEQ, and Storm-Water Mandates

Under the Clean Water Act, the EPA regulates storm-water runoff from urbanized areas, regions with 10,000+ residents and high density, including parts of South Logan County, through the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) (33 U.S.C. §1342). The EPA’s Phase II rules (1999) require small municipal separate storm sewer systems (MS4s) to obtain permits and develop Stormwater Management Programs (SWMPs) with six best management practices (BMPs), such as public education and pollution control (40 C.F.R. §122.34). In Oklahoma, the DEQ enforces this via the Oklahoma Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (OPDES), issuing OKR04 permits under 27A O.S. §2-6-202. Non-compliance risks federal penalties, but compliance costs, $748.11 annual DEQ fees plus millions for BMPs, burden local taxpayers.

Logan County’s federally declared urbanized areas, though modest compared to Tulsa, fall under this mandate, prompting Cole and Sharpton to propose hiring WSB Engineering for a minimal SWMP. Cole insists that WSB, a Minnesota-based firm with an Oklahoma City office, is the only vendor capable, justifying a sole-source contract that sidesteps competitive bidding under 19 O.S. §1505(B)(6). WSB’s LinkedIn job posting on June 12, 2025, seeking a Water Engineer with expertise in “comprehensive water system plans” and CWA compliance, suggests the firm anticipates a boom from Oklahoma’s MS4 mandates. Posted just a day before this board meeting, this timing fuels suspicions of a prearranged deal, providing additional support for Chairman Piercy’s call to resist federal overreach and protect Logan County’s autonomy.

The WSB Contract: A Divisive Proposal

At the June 13, 2025, Logan County Board of Commissioners meeting, Troy Cole, the county clerk and purchasing agent, pitched the $18,500 contract as a necessary response to DEQ’s pressure for an OKR04 compliant SWMP. “Only WSB can deliver this plan,” Cole claimed, citing the firm’s expertise in navigating EPA and DEQ regulations. Mark Sharpton, District 1’s commissioner, backed the proposal, warning of federal sanctions if Logan County delays. Yet, Monty Piercy, District 3 commissioner and board chairman, fiercely opposed the contract, arguing it surrenders local control to federal/state bureaucrats and wastes taxpayer dollars on a state enforced federal mandate.

Sole-source contracts, allowed under 19 O.S. §1505(B)(6) when only one vendor is viable, require rigorous justification and board approval. Cole’s assertion that WSB is uniquely qualified lacks scrutiny, firms like Carollo Engineers or EST Inc. in Oklahoma City offer similar services, and national competitors could bid if solicited. WSB’s job ad, seeking a Water Engineer with 5+ years of experience in storm-water planning, signals confidence in securing contracts like Logan County’s, suggesting profit-driven growth tied to the Oklahoma DEQ mandates. Piercy’s opposition highlights this coincidence, questioning whether WSB’s selection serves Oklahoma or federal interests.

The $18,500 price tag, though modest compared to other MS4 costs, rankles conservatives wary of federal-driven spending. A “minimal” SWMP may satisfy OKR04’s bare requirements but risks future DEQ demands for costly upgrades, like green infrastructure or monitoring systems. Piercy argues that Logan County should reject the contract. Constitutional conservatives recommend the County should leverage the Supreme Court’s Loper Bright ruling to challenge the mandate’s necessity, aligning with Oklahoma’s state’s sovereignty ethos.

Loper Bright: Oklahoma’s New Weapon Against Federal Overreach

The Supreme Court’s Loper Bright decision (June 28, 2024) overturned Chevron deference, ending judicial deference to agency interpretations of ambiguous statutes (603 U.S. 369). Under Chevron, the EPA’s broad reading of CWA terms like “point source” or “urbanized area” bound states, with courts upholding rules if reasonable. Now, courts interpret laws independently under the APA (5 U.S.C. §706), applying Skidmore deference, non-binding respect for agency expertise, if persuasive.

This empowers Oklahoma to challenge EPA mandates lacking clear CWA authority. Our Attorney General could pick up this mantel, but don’t hold your breath, after all it is an election year and he is mostly focused on running for Governor than doing his current job.

For Logan County, Loper Bright is a clarion call to resist the DEQ’s OKR04 mandate. The EPA’s storm-water rules, rooted in ambiguous CWA provisions, are vulnerable. Terms like “urbanized area” or “maximum extent practicable” for BMPs lack precise statutory grounding, inviting judicial scrutiny. A pending case, City and County of San Francisco v. EPA (2024), where San Francisco contests EPA permit conditions post-Loper Bright, offers a blueprint for Oklahoma. The DEQ could argue that the EPA’s MS4 requirements for small counties like Logan exceed CWA authority, freeing local governments from costly plans.

Yet, Cole and Sharpton’s push for WSB’s contract prioritizes compliance over defiance. Cole’s sole-source rationale, untested by bids, dismisses Loper Bright’s potential to loosen federal shackles. Sharpton’s support, despite his error-prone history, risks entrenching Logan County in a federal framework, with WSB poised to profit from DEQ-driven growth. Piercy’s opposition, rooted in conservative skepticism, demands the DEQ justify the mandate before taxpayers foot the bill, aligning with Oklahoma’s fight for local autonomy.

Oklahoma’s Sovereignty: Piercy’s Stand for Freedom

Oklahoma’s conservative legacy, anchored in the Ninth and Tenth Amendment principles, rejects federal overreach. The EPA’s MS4 program, enforced by the DEQ, epitomizes Washington’s one-size-fits-all tyranny, imposing urban mandates on counties like Logan, where rural roads dwarf storm drains. Loper Bright hands Oklahoma a sword to reclaim sovereignty, as courts can reject EPA rules lacking clear CWA backing. Chairman Monty Piercy, a steadfast conservative, embodies this resistance, opposing the WSB contract as a capitulation to federal bureaucrats. His call to challenge OKR04 aligns with Oklahoma’s history of defying EPA air rules or HHS mandates.

The Sooner Sentinel stands with Piercy, urging Logan County to dismiss the sole source WSB contract and demand the DEQ justify OKR04’s statutory basis. If needed, competitive bidding, per 19 O.S. §1505(B)(2), could expose cheaper alternatives or reveal the mandate’s fragility. WSB’s job posting, touting storm-water expertise, suggests a firm banking on federal compliance, not local needs. The DEQ, while bound by EPA delegation, could seek a federal injunction against OKR04’s terms, citing Loper Bright and the major questions doctrine (West Virginia v. EPA, 2022).

The Environmental Facade: Local Solutions Trump Federal Mandates

EPA proponents claim storm-water rules protect Oklahoma’s waterways, like Cottonwood Creek, from urban runoff’s pollutants, sediments, oils, and chemicals. Justice Elena Kagan’s Loper Bright dissent warned that gutting Chevron threatens environmental safeguards, as agencies wield technical expertise. But this narrative dismisses Oklahoma’s capacity to manage its waters without federal dictation. The DEQ’s Water Quality Division (27A O.S. §2-6-105) monitors local water-bodies and could craft tailored controls, free from EPA’s urban bias. Logan County’s minimal plan may check a box but risks failing local ecosystems while draining funds, as WSB’s growth signals profit over progress.

Logan County’s Crossroads: Defiance or Surrender?

The Logan County Board of Commissioners faces a defining choice: eventually approve WSB’s $18,500 sole-source contract or heed Monty Piercy’s call to resist. Troy Cole’s unverified claim of WSB’s exclusivity demands scrutiny, bids from firms like EST Inc. or Carollo Engineers could lower costs or expose OKR04’s flaws. Mark Sharpton’s compliance push, clouded by past errors, risks squandering taxpayer trust. Piercy’s leadership, backed by voices like Floyd Coffman, offers a chance to challenge the DEQ in court or negotiations, leveraging Loper Bright. Logan County Oklahoma taxpayers, from Crescent’s historic heart to Commission District 1’s urbanized growth, deserve a board that fights for sovereignty, not one that funds WSB’s federal-fueled profits.

The Sooner Sentinel urges our liberty minded State Representatives Molly Jenkins, and Jim Shaw to take note of this important issue and for local readers to pack board meetings, demand transparency, and champion state’s rights, ensuring Oklahoma’s future remains as free as its open plains.